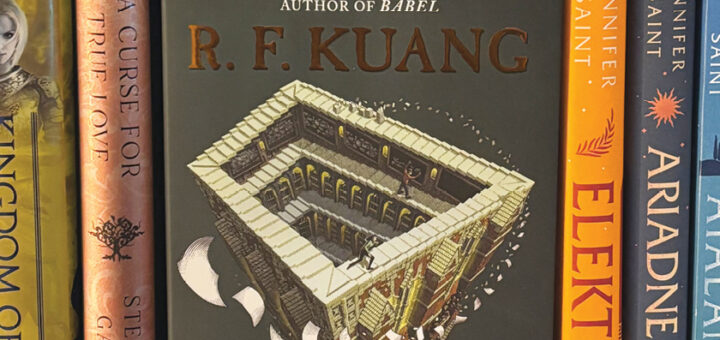

Reviewing R.F Kuang’s Katabasis

Rylie Perry, Arts Editor

Released on Aug. 26, Katabasis by R.F Kuang is one of the most anticipated releases of the year.

The novel, which marks Kuang’s sixth book publication since 2018, follows two rivaling graduate students who undertake a journey to Hell to retrieve their recently deceased professor’s soul.

Alice Law, brilliant, yet insatiable, has given everything that remains of her mind and soul to the field of Magick—if degradation is the cost of academic success, Alice has paid her dues in full.

Peter Murdoch, a prodigious magician since childhood, was born with a silver spoon in his mouth. While his talent is undeniable, the inborn advantages that tip the scale his way are tenfold.

With the untimely death of their professor, Jacob Grimes, ripping their Cambridge recommendations down to hell with incorporeal hands, Alice and Peter refuse to let even death separate them from their futures.

While the novel’s release comes at a time when fantasy and dark academia are the pinnacle of genre popularity, Katabasis is in a league of its own.

A Marshall scholar, Kuang received her undergraduate degree in History from Georgetown University, a MPhil in Chinese Studies from Cambridge University, and a MSc in Contemporary Chinese Studies from Oxford University. Now, Kuang is pursuing a PhD in East Asian Languages and Literatures at Yale University.

It is no surprise then that Katabasis’ rendition of Hell is deeply rooted in the literary and philosophical genius of Dante, Orpheus, Virgil, and T.S Eliot, which Kuang neatly places in a mathematical and logical framework.

Kuang, however, is not concerned with showing readers her merit as a scholar; rather, she constructs a hellscape that, while reliant on scholarship, reflects the very real infrastructural shortcomings of academia and bureaucracy.

“‘Christ,’ said Peter. ‘Hell is a campus.’”

By definition, Katabasis is a Greek term that refers to a hero’s journey to the underworld, driven by a definitive goal or purpose. However, Katabasis can also refer to story structures that portray characters attempting to rise from their lowest moments.

“I was very interested in this metaphorical, psychological journey when you have reached a point in your life where you feel like it’s no longer worth living,” said Kuang in an interview with Waterstones. “What would it take to climb out of that?”

At its core, the novel is a deeply personal exploration of purpose and the search for resolution, which grapples with defining indefinable concepts, such as life, death, and the intersectionality of memory and identity.

“And if you could constantly reinvent yourself, cut away the parts of you that ashamed or hurt you, then how could you ever come to really know someone else?”

Although the world Kuang constructs is confident and striking in its own right, the backbone of the novel is undoubtedly the characters. The hellscape she produces confronts characters with the depraved indifference of traditional systems and what the decline of Hell’s infrastructure represents for each of them.

Even the Magick system functions as a narrative tool to convey the paradoxes that work to destabilise and rebuild Alice and Peter’s understanding of meaning and purpose, which is reinforced by the almost clinical application of logic, analytics, and mathematics to the occult.

“But that was precisely what magicians lacked; there were no honest words, only puns and illusions and constructions of reality.”

Above all, the novel grants precedence to Alice’s journey. She is an extremely nuanced and flawed character that struggles with justifying her own moral ambiguity, which makes her a complex, if not likeable anti-hero.

Throughout the book, she wrestles with her need to remain emotionally distant within a professional world that sets her a rung below her peers, all the while desperately craving the academic validation that continues to build her up, only to break her back down again.

“As if he were coaching her to run a race they both knew she’d already lost.”

Peter, however, is a character that functions seemingly in Alice’s peripheral vision, but displays startling clarity and depth when the novel allows him to. He is charismatic, intellectual, and privileged, but breaks through the fog of Alice’s narration with shining moments of vulnerability that enable an ever shifting power dynamic between them.

While Alice and Peter’s relationship is indisputably important to the integrity of the novel, romance does not seem to be the point. Rather, they function as an ambiguous pairing that serve one another’s personal explorations of selfhood, not as an inevitable romantic duo.

As a whole, Katabasis is clever and painfully raw, exposing the twisted underbelly of an academic world that Kuang knows intimately. The novel is not self-righteous, however, but meditative and introspective.

Alice and Peter tackle themes of grief and self-discovery with vulnerable hands, shaping and re-shaping their imperfect, broken identities through the Katabasis story structure.

Katabasis is thus a brilliant novel that stands firm as one of the best books of 2025, if not of the last few years.