Exploring the front lines of war journalism

Bella Coco, News Editor

When Brooks Decillia was in seventh grade, he was asked to write a report on any country of his choice. Little did he know that this country would follow him from elementary school to his career as a CBC war correspondent.

Decillia put his hand up to report on the conflict in Afghanistan back in 2006, hoping to achieve his goal of becoming a foreign reporter with hot-zone experience. When Canada decided that deployment to Afghanistan was a critical mission, Decillia knew he had to be there.

“Journalists have an obligation to tell those stories about why those forces are being deployed and what’s happening, and to be observers and documenters of the conflict. I thought it was important for journalists to be in Afghanistan and tell stories about what the soldiers were doing there and why they were there,” Decillia said.

Despite entering the conflict with hostile-region training and prior reporting, Decillia says there was no way to be truly prepared.

Decillia’s first actual moment of fear revealed itself on base at the Kandahar Airfield when sirens blared a warning of incoming missile strikes.

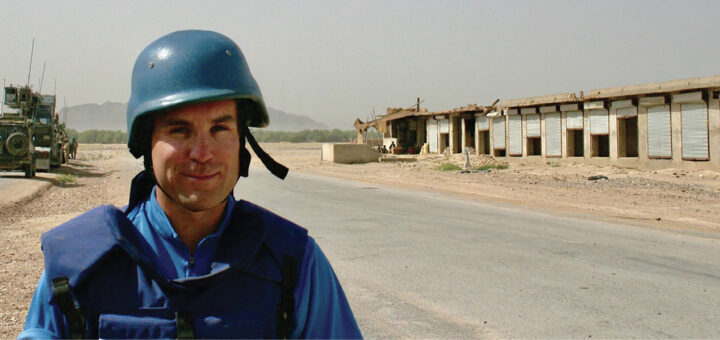

Decillia working on a story back on base. Photo supplied by Brooks Decillia

Despite the insurgents’ inaccurate missile targeting, the idea of being in the wrong place at the wrong time stuck with Decillia before he even started his correspondence.

“Sometimes they would hit the airfield, or they’d hit a field, or they would completely miss where the sort of tents or the buildings were that we were working in. But some of them did. A few weeks before I got there, or even the week before I got there, I think they hit the sort of main cafeteria, and some people were injured,” Decillia said. “So the first time I ever heard the siren, I’ll be honest, it sort of freaked me out and scared me, but I had the presence of mind to, you know, get to some of these bunkers that they’d set up, or sort of shelters that they’d set up under concrete.”

The siren calls eventually became a daily routine for Decillia, but the blare of danger followed him home as well.

“I was walking in Covent Garden in Central London, and someone dropped a whole bunch of garbage down a chute, and it made a large noise. It scared me, and I sort of dropped to my knees, not almost to my knees, but, you know, it scared me to the point where I was getting down in front of a bunch of people who were a bit bemused why this man was on the ground after that loud time,” he said. “Still, you’re so conditioned to get down low when you hear the siren or [when] you hear the whiz or the whistle of rockets. So you kind of knew that you needed to get down low.”

Despite the “normalised” daily dangerous routine, Decillia’s job was no walk in the park. An automatic target was strapped to his back when he went on patrol with Canadian forces, and the primary concern at the time was the threat of improvised explosive devices (IEDs).

Decillia said that while the question of safety while patrolling with the infantry or even the artillery makes the beat complex, staying objective in war journalism also proved to be a challenge.

“It’s also complex in terms of thinking about how you report on something. Because if you think about general reporting, you’re trying to be fair and balanced and accurate and all those sorts of things, but when you’re embedded with Canadian forces, really, you’re only seeing the war or the story from one side,” Decillia said.

Finding the other perspective by interviewing insurgents could prove deadly, so Decillia and other reporters had to get creative. By seeking help from Afghan interpreters or even contacting a spokesperson for the insurgents, Decillia found a way to maintain balanced reporting.

However, even with playing fair, it didn’t always mean everyone was happy with the work that was published.

Decillia remembers the first time he received backlash from the military and the government, and the first time tension leaked out of the lede and into his life.

“I started my story with some video of gunfire, and I said, ‘This is definitely not peacekeeping,’ because I think a lot of Canadians assumed that Canada would be peacekeeping. This was very early on in the days of a conflict in Kandahar between the insurgents and the international stabilising force, and I used a clip of a young private,” he explained. “I asked him, ‘You know, how did it go today?’ And he said, ‘It was really great. We finally got some payback.’ The concern was that maybe the soldiers seemed a bit bloodthirsty. I don’t think he was, and I think it was a fair question.”

In a time of conflict and immense patriotism back home, Decillia noted how fair reporting could have been seen as being “disloyal to Canada” from an outsider’s perspective.

“Aeschylus, the sort of ancient Greek dramatist and veteran, said, the first casualty of war is the truth, right? So sometimes it’s hard to sort fact from fiction,” he said.

Decillia said that it was easy to be misled by optimistic updates from the military, with officials often stating that they were restoring safety and security.

However, when journalists saw no improvement on the front, they began fact-checking in real time.

Despite reporting the truth and even getting critical of the government, Decillia’s understanding never left his reporting.

“I think empathy is at the core of journalism. I think you need to bring empathy, particularly, because I think you can get cynical because you’re in a situation where people are dying. It’s life and death. You do need to remember that these are human beings,” he explained.

After his time in Afghanistan, Decillia began to view remembrance through a new lens of appreciation.

Canadian soldiers perform a ramp ceremony for their fallen comrades. Photo supplied

by Brooks Decillia

“I came away from Afghanistan with a respect for why people serve in the military and what motivates them to serve, and this profound sense of giving selflessly and being willing to put their lives on the line,” Decillia said. “To serve unselfishly and put pride in Canada and their pride in doing the work that they did and the pride in the history of the Canadian military and the history of the Canadian Armed Forces.”

While the experience was a takeaway for Decillia in his professional career as a journalist, he also walked away with newfound knowledge on those who served and lost their lives for their country.

“I had the honour or the duty of reporting on a number of ramp ceremonies, when Canadian soldiers are repatriated. There’s a ceremony before Canadian dead soldiers are sent back to Canada, and those were very moving. I saw these big, burly soldiers with tears in their faces, carrying their dead comrades’ bodies and flag-draped coffins onto military transport to take them back to Canada. Right? I thought that was a very moving experience, so the ramp ceremonies and the bagpipe music sticks with me.”