Why Mount Royal University’s growing Indigenous student population is significant

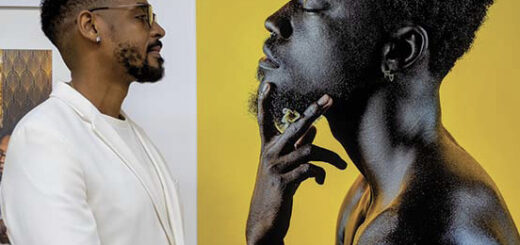

Nikita Kahpeaysewat is a second-year environmental science student from Moosomin First Nation, Sask. This past spring she attended the American Indian Science and Engineering Society Summit where her university journey was featured in the Winds of Change magazine. Photo courtesy of Blaire Russell

By Andrea Wong, Contributor

MRU has never seen more Indigenous students than those walking on campus today. In the last five years, the number of self-identified Indigenous students has more than doubled to 800 and for the first time has reached a higher retention and graduation rate than non-Indigenous students.

It’s a milestone worth celebrating, but the successes along the way stir a greater appreciation for how these students got here and where they are heading.

Navigating the university system

Historically, assimilation and systemic racism has permeated numerous sectors of Canadian society, and the post-secondary institution is no exception. Until the 1960s, under the Indian Act, if an Indigenous person attained a university degree their Indian status would be taken away, which meant losing their treaty rights and connections to family and community.

The lack of support services posed another barrier to higher education and made post-secondary institutions “impossible to navigate,” says MRU alumni Steve Kootenay-Jobin from Stoney Nakoda nation.

When he first stepped into the halls of MRU in 2007, Kootenay-Jobin was the youngest amongst a few other Indigenous students. With little support on campus and many of his peers dropping out, Kootenay-Jobin often felt alone and hopeless.

“Indigenous peoples have specific needs. We need to be able to feel like we have a sense of belonging [and] a sense of identity,” Kootenay-Jobin says.

Creating space for Indigenous students

Today, Kootenay-Jobin works in the Iniskim Centre as the Indigenous housing coordinator. He says he is very happy to see a positive shift as hundreds of Indigenous students attend MRU.

He attributes this change to the university’s Indigenous Strategic Plan and commitment to reconciliation.

MRU was one of the first universities in Canada to adopt the Indigenous Admission Policy, which reserves seven per cent of all program seats for incoming Indigenous students. The policy makes room for students who meet the minimum requirements but might not be at the competitive average.

While some may think those seats are being “tossed around as perks or privileges,” Kootenay-Jobin says it allows opportunities for first-generation university students to break through barriers of trauma and discrimination.

“Many people, unfortunately, don’t feel secure in continuing on in schooling if they’re consistently told no,” Kootenay- Jobin says. “We are reducing barriers. We’re opening up the doors and our institution is showing a commitment to reconcile but also address the inequities and the inequalities of the past.”

Building bridges

The Iniskim Centre has also expanded to a robust “one-stop-shop” that provides community and brings together resources that help students navigate university in a culturally safe space.

The Indigenous University Bridging Program, in particular, plays a key role in helping new students transition into university. That’s how Nikita Kahpeaysewat, whose Cree name, Usinee Iskwew means ‘Rock Woman’ in Plains Cree, found her place at MRU.

Originally from Moosomin First Nation, Sask., Kahpeaysewat had been out of high school for about three years when she decided to move and go to university. While she was upgrading through the Indigenous University Bridging program, Kahpeaysewat had academic support from tutors, as well as program director Tori McMillan. With their help, Kahpeaysewat was able to succeed and eventually discovered a love for science.

“When you provide an opportunity, you’ll see the best come out of people, you’ll see them thrive,” McMillan says. “That’s the story here in our school. The students are thriving because they have a community here and through that sense of belonging, it carries them through the challenges of being a student.”

Kahpeaysewat is now in her second year of environmental science and has attended national conferences such as the American Indian Science and Engineering Society Summit, where they featured her in their magazine.

“If somebody would have told me that I’d be in science and I’d like school back when I was in high school, I probably would have laughed because it was the complete opposite back then.

“I didn’t have the drive to do well in school,” Kahpeaysewat says.

However, none of these opportunities would be possible without the support she received.

“If it wasn’t for the people at Iniskim guiding me, I feel like it would have taken me a lot longer to figure it out. And maybe by then, I would be struggling so much, I wouldn’t want to stay.”

Beyond the walls of university

While Kahpeaysewat has gotten “really comfortable as a student,” she has plans to work in research and policy where she hopes to impact Indigenous communities like her own concerning water quality.

It is aspirations like Kahpeaysewat’s that Indigenous recruitment officer Melanie Parsons says MRU aims to build. While speaking to Indigenous communities across Canada, Parsons shares her own university experience as a Cree Métis woman and inspires students to consider the possibilities of higher education.

“There is a safe place for Indigenous students at Mount Royal … where they can make something of themselves and make their dreams come true through education and experience,” Parsons says.

As more Indigenous people go to university, they also bring their friends, family members and communities.

For Kootenay-Jobin, two of his brothers followed after him, and it is a reality that his nephew has grown up seeing.

“Education is no longer a ‘what if’ factor [or a] ‘do I have what it takes?’ It has become normalized for my nephew now, where it’s ‘when I go to university.’”

Parsons agrees, adding that as more Indigenous people move into different roles and work in their communities, they will inspire others to do the same.

“The more people that are getting their education the better, so that we can have Indigenous doctors and teachers and social workers,” Parsons says. “It’s about creating an opportunity for yourself [and] creating opportunities for your community.”