Faith Column: Spirituality and sports

Everything has a price

James Wilt

Faith Columnist

The news flooded the airwaves and Twittersphere within minutes. The NHL lockout was over. A collective breath was expelled, finally. Canadian life could begin again.

The fervent response was pretty understandable, considering that ardent fans had to endure a 113-day period during which owners and players clashed over contracts, leaving them with little reason to suit up in their $300 jerseys.

People were really excited. Almost disturbingly so.

Then, the Globe & Mail published a story titled “Canada’s church of hockey ready for mass again,” and it all started to make sense.

Of course, parallels between spirituality and sport aren’t exactly new; anyone who’s watched Friday Night Lights is fully aware of the “football is a religion in Texas” adage, for example.

But there was something just so much more significant about this particular situation, perhaps because it happened so much closer to home.

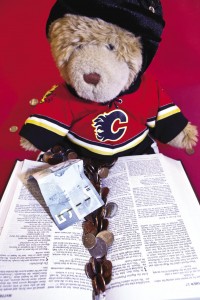

The one thing that connects the NHL, religion and cold hard cash — Build-A-Bear. You heard it here first, folks. Photo Illustration: James Wilt

There’s a staggering amount of allegiance to the NHL in Canada, as there is any major-league sport.

The Globe & Mail story emphasized that fact when describing the significance of the lock-out’s conclusion: “What happened on Sunday morning in the dawning days of 2013 restored a piece of their lives that had gone missing, leaving something off-kilter.”

Enthusiastic descriptions like that can usually only be compared to religion.

But writing a column dedicated to such a subject would be a tad redundant, considering there’s been a plethora of work dedicated in the realms of sports psychology to the association.

Perhaps more interesting in this instance is the enormous amounts of money involved in both aspects of the comparisons, and how it’s particularly associated with the notion of tribalism.

Both sports and organized religion rely on gargantuan budgets, which is why they need you and me.

Such institutions are profitable entities, no matter how you want to spin it. It’s blatantly obvious with the NHL — Forbes estimated near the end of 2011 that the average team was worth $240 million. Player salaries are staggering. Owners make even more.

But religion is perhaps just as profitable. Of course, that’s not the case for the individual preacher, imam, rabbi or monk.

It’s the religious organizations, unlike the entry-level employees, that are the massive money-makers.

Weekly tithes, donations, tax-exempt statuses, huge ownership of assets, and crime (here’s looking at you, Scientology) all feed into that, just as jerseys, beer, tickets and Pay-Per-View keep the NHL afloat.

But here’s the crux: both organizations need tribal-oriented followers to retain profitability. It sounds cynical.

However, it’s tough to deny the good intentions that inspired the creation of both have been brutally co-opted by capitalism, tragically re-defining their reason for existence.

We, as consumers, serve organized religion and the NHL in the same way. The divisions created by tribal mentality — teams in sports and denominations in religion — assist in this enterprise, as it distracts us from the common reality that we’re being completely exploited by such institutions.

Psychology Today once declared that sports were the new “opiate of the people,” serving as a form of “cultural anaesthesia” and “spiritual masturbation” that distract from the real issues of today.

It doesn’t have to be like this, though. Both spirituality and sport were well-established as parts of society that were considered to better our collective experience of this odd thing called life, far before money became the focal point.

Those places still exist. It’s in the outdoor arenas where kids play shinny for fun rather than for the cheques.

It’s even in the farm-team locker room, although their noses are a tad closer to the prize of making it to the big leagues.

It can be found in religion, too. It’s in the informal meet-ups. The library books that transcend strict doctrine.

Coming together from different traditions to share understandings of truth.

Ultimately, it’s that spirit of doing things collectively — whether it be praying or shooting pucks — that can still overcome this vile infatuation that both religion and sport have developed with profit.

But it requires action from us. Perhaps boycotting the first Flames game — or all of them — might be a good first step.