Weighing the fine line of true crime TV

Alexandria Smith, Contributor

There is a chance you have either seen or heard of Monsters: The Lyle and Erik Menendez Story. If not, you are an outlier among the 12.3 million viewers who watched it on Netflix.

The true crime genre, which started on the pages of literature, has made its way to the screen and even our ears via podcasts. In 2024, Vogue listed the top 50 to listen to at the time—clearly, there is a lot of true crime content that is being consumed.

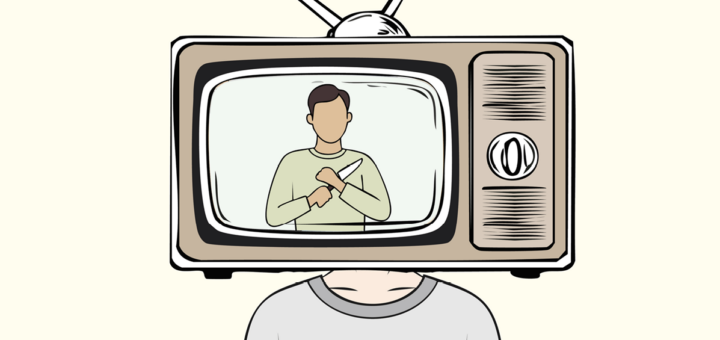

But with anything, when popularity rises, as does the scrutiny it receives. In the case of the true crime category, one Mount Royal University (MRU) professor questions whether it’s having a positive or negative impact on audiences.

Captivation of crime in the media

Coupled with her interest in researching the public perceptions of crime, criminal justice professor Tanya Trussler who lists her research interests as causes of violent crime, crime prevention, and public perception of crime.

With the surge in viewers consuming true crime content, Trussler wonders why people are so interested in it in the first place. As humans, she says that “we want answers to the unknown,” and that the genre—unsolved cases, mysteries, and violence—gives that thrill.

While the allure has long been there, Trussler says that what’s different today is how people can cozy up in bed to a lineup of shows like Monster: The Jeffrey Dahmer Story. She emphasizes that watching the violent crimes Dahmer committed is part of the appeal.

“We cannot understand why somebody would do something like that,” she emphasizes.

Trussler says that the fear factor is just a portion of what gives true crime its allure. She says that for women, who make up the majority of viewers, the genre gives them a sense of justice.

“Women want to listen to it because they have been a dominant victim,” she says. “But then it creates more of that transgression…it perpetuates in their own mind that they may be the victim.”

The positives and the negatives

Trussler says that today’s overwhelming number of streaming platforms has transformed the media away from solely cable services. As a result, she says that the genre has thrived in bringing old cases to the attention of law enforcement.

“There’s more spotlights, not just one spotlight from the mainstream media or one push from the police,” says Trussler. “It’s actually, ‘Oh, the police aren’t doing anything, so I’m going to tell them about it.’”

In 2021, for example, while filming The Jinx—a two-part HBO series following the life of Robert Dunst—evidence was revealed linking Dunst to a 20-year-old unsolved murder, according to a report by the Associated Press.

Additionally, true crime can be regarded as an educational genre, as the sheer amount of podcasts, shows, and documentaries provides an array of perspectives that viewers can interact with.

Upon engaging with a story, viewers may go even further by doing their own research. While this is healthy when adding to the critical conversation of crime, Trussler says that some creators turn murder stories into money-making pawns.

“In the case of podcasts, they have catchphrases, and they’re making merchandise,” she says.

Hosted by Karen Kilgariff and Georgia Hardstark, the podcast My Favorite Murder, which garners approximately 35 million monthly listeners on Spotify, sells t-shirts and other items for upwards of $40 USD a piece—something Trussler says is discouraging.

“It takes away from the victim’s stories,” she says. “If you’re commodifying it and using it as a way to fundraise or something…that’s great, but I don’t think that’s where this is going.”

If, in the same breath, audiences are being sold a product, are they really gaining insight into the heavy topic at hand?

In 2022, the British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC)’s Hugh Montgomery explored Director Ryan Murphy’s Monster: The Jeffrey Dahmer Story. The first half of the show focuses on his past, showcasing the abuse he endured and what led him to commit the violence that he did.

What the BBC and critics of the show agree on is that the glorification of Dahmer translates as neglecting his victims’ stories. By centring the genre around the perpetrators, the article discusses how the media forgets that true crime is meant to amplify what the victims went through, not spotlight the wrongdoers.

Striking a balance

Is it safe to say that true crime media is all good or all bad? Can we fit the genre into one box? True crime and its presence in the media do not seem to be going away, so is there a solution? Not according to Tussler.

“There is no answer,” she says.

For the many women listening to true crime podcasts, Tussler says the media often makes the indulger feel prepared, which can be seen as a positive. However, as they delve deeper into the genre, feelings of fear can spill over into their daily lives.

“The things that we see in the media are not necessarily what is the common experience,” she says. “We’re actually way more likely to be the victim of sexual assault during a date or [by] a family member…not the stranger in the corner.”

Tussler says that the genre shows no signs of slowing, and recommends that viewers draw their own balance by taking a step back and looking at their reason for interacting with the genre: are they a commodity, or a critical thinker?